“Is it possible to think in public?” asks Jemma Desai in her desktop documentary What do we want from each other after we have told our stories? Desai is a researcher, teacher, and reluctant artist born and raised in London. She is also a former film programmer and my dear friend.

In June 2020, Desai released This Work Isn’t For Us into the public domain. A vast Google Doc, it recounts her firsthand experiences of institutional racism in the UK film industry, and includes testimonies from other cultural workers of color who also, in her words, “navigate toxic white supremacy every day.”

She writes with staggering clarity about the culture of racist malpractice disguised as “diversity” and “inclusion” and peddled by her former employers. Technically speaking, This Work Isn’t For Us is a research paper, written over an 18-month period and funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, with additional support from a Clore Fellowship Desai received in 2018. Still, “research paper” feels like an inadequate way to describe the grace, poetry, and fierce critique the document contains.

Neither does the term account for the array of crossmedia reckonings and offshoots the project has sparked. Six months before releasing the document, in January 2020, Desai wove readings related to and excerpted from the research into a performance (a kind of illustrated lecture) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts as part of the London Short Film Festival. Desai shared and reflected on her experiences of dissonance and alienation as a brown person working in predominantly white and supposedly liberal arts organisations. Audience members were given notepads and invited to use the space to reflect, too.

The performance was followed by three generative online conversations hosted by international arts agency LUX as part of the dissemination of This Work Isn’t For Us. These put her in dialogue with people who had shaped the research: art critic Zarina Muhammad; educator and activist Aditi Jaganathan; and filmmaker, curator, and DJ Rabz Lansiquot.

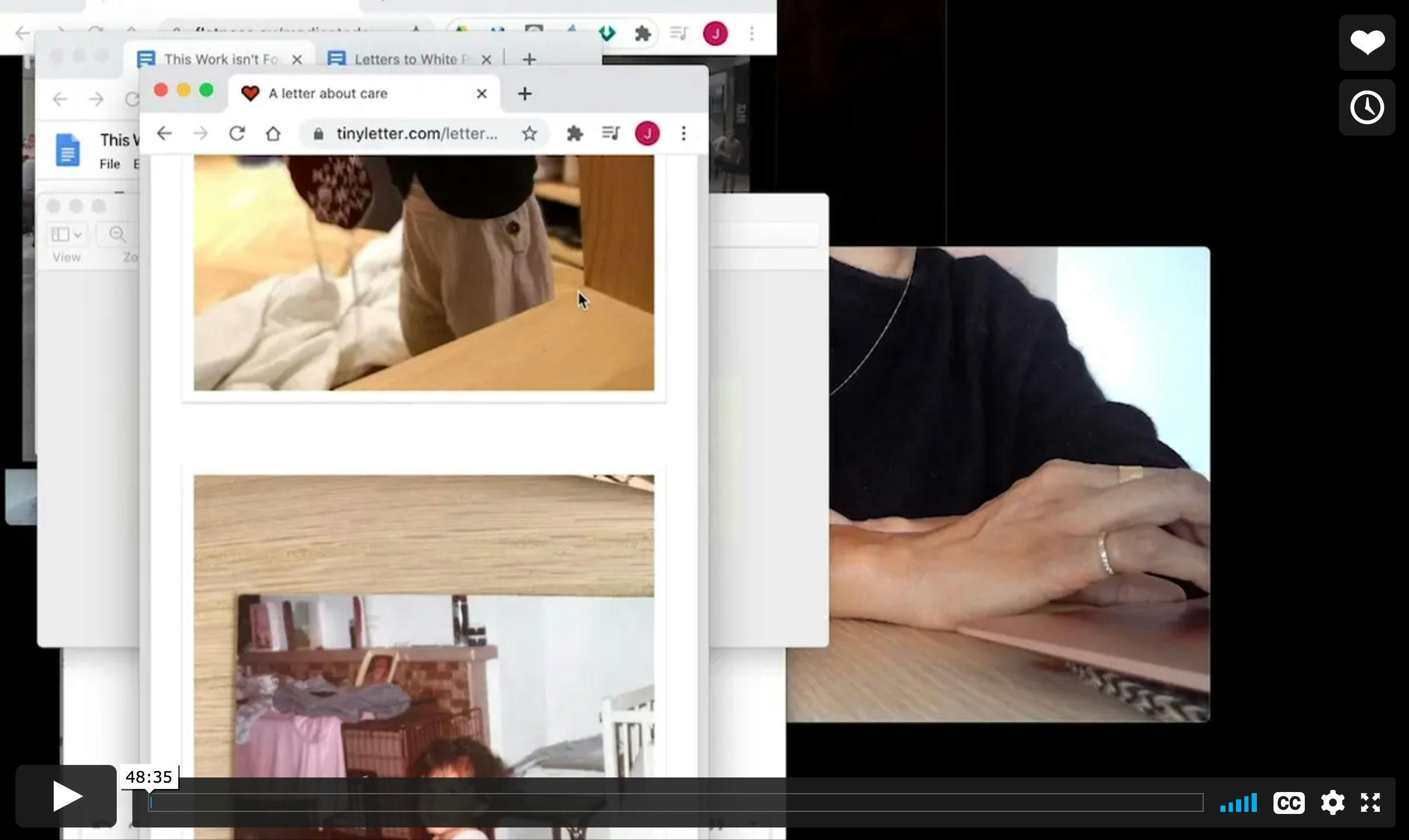

The desktop documentary What do we want from each other after we have told our stories? is a kind of contemplative companion piece to these talks—a conversation between Desai and herself in the form of a 50-minute video piece set against the backdrop of her computer screen. Premiered online via LUX in August this year, the documentary ruminates on the difference between making her work public and having a public conversation. The piece comprises AirDropped voice memos containing Desai’s narration, a Reddit thread on the storied history of her house in East London, and video clips, such as an excerpt from Alnoor Dewshi's 1992 short film Latifah and Himli's Nomadic Uncle. One sequence features a Google Doc called “Letters to White People,” containing emails to her white therapist, an all-white mutual aid group, and her white employers. “The Google Doc has given up,” she says wryly of a notification that reads “pages unresponsive.”

In the following conversation, recorded over Zoom on a Friday night in November 2020, Desai returns to the piece, and together we think through the value of sharing in public, documentary practice as a strategy of refusal, and film as a portal into a new way of being.

You describe this piece of work as “about anger and healing and taking up space, in words, in buildings, in private, in public.” That’s what it’s about, but what is it, in your mind? Is it a performance, a curation, a piece of criticism?

I think what you call something, or what you think something is, is so situated on what you think you are. If I had decided I was an artist, I would call it a performance, or if I’d decided that I was a video essay–maker, then I would say it was a video essay, or if I thought I was a filmmaker, then I would say it was a film.

Before making the piece, I went away and took mushrooms, which were grown in our house, in our kitchen. A lot of the aesthetic of that piece came from what happened on that trip. This piece of work became a way to process that trip, but the trip was a way to process all of the stuff that had happened in the last few years [of doing the research]. The trip was like six months of therapy in six hours.

Someone got in touch with me and was like, “It’s a desktop documentary,” and I was like, “Oh, I suppose it is,” but I’d never even heard of that term. I’d never seen one; I hadn’t seen Zia Anger’s performance [My First Film].

My First Film also sits somewhere between performance and “desktop documentary”: there are definitely commonalities in how you both process the harm that has been done to you in order to protect others. Your original performance was called Autoethnography as Refusal, which I think is interesting given the documentary form’s roots in ethnography, and the decolonial nature of your project.

As a concept, [autoethnography] is about looking at the self in order to understand the world, but I feel like it’s someone else’s word. Still, the concept of using the self to refuse that objectification, or that disembodiment, is 100% the driving energy behind the written research, and also this piece. In nonfiction filmmaking, there’s also a real denigration of the voiceover, a real denigration of the self, a denigration of the “I” of the personal documentary. As a programmer, I have heard so much that autoethnographic filmmaking is not serious filmmaking—that it’s like “diary” filmmaking, which is so often [associated with] white women. There’s so few diary films from Black women and more broadly from women of color.

The recording was a strategy: it was a way of me not having to do it live. I recorded it so I could get it right. It wasn’t supposed to be a piece of work.

To me it feels so complete and full that to hear you describe it as an accident of circumstance is, like, wow!

I think there’s something about this which really reflects what happened accidentally with This Work Isn’t For Us. I didn’t know it would be shared on a Google Doc, but now it means something that it was shared on a Google Doc. In the same way, I didn’t know this would be a recording of my screen, but because of the constraints of the time and my capacity and everything, now it means something that it was. If I had gone to a publisher and asked for permission to write a book, I wouldn't have been able to refuse certain things, whereas now [that] it’s a Google Doc, no one can change it or make me change it [and] I have all this autonomy. There’s this refusal within that. It’s the same with this desktop documentary.

I’m interested in the ways in which you protect yourself in the work. Your use of first-person narration, not to mention the personal nature of the things you talk about, makes it feel so vulnerable, yet we never see your face. We see your hands and your torso and we see your arm. The critic Tara Judah wrote that we see your arm having a rest after writing 54,540 words. Was that a strategy of refusal as well?

In a way, disembodying my visual image allowed me to be more embodied and liberated in my voice. Voice was a really important theme of the research and I found my voice—not just in the writing, but I found my physical voice.

The live performance at the ICA was partly to do with that. Like, wow, I’m gonna actually say this stuff in public and I’m gonna try and deliver it in a voice that holds some power and doesn’t trail off at the end. So many things had been said to me: that I didn’t make sense, or I wasn’t speaking up. What are the conditions in which your voice can be steady and articulate and clear? At the time [of making the desktop documentary], the conditions in which my voice could be strong required a level of obscuring.

Your strategies of refusal in the piece connect with a line from the research that you quote: “Everyone says it was generous and it makes me wonder if I gave away more than I know.” Maybe it’s your way of reflecting on that idea of generosity, and maybe this time you’re more aware of what you’re giving.

There’s a line between oversharing and making a piece of art, and I don’t know where that line is, but it should come from you—it shouldn’t be imposed on you from the outside. I think I’m just really coming to know that the openness with which I’d shared [the research] hadn’t been cared for by everybody.

And so I think there’s two things about this piece. One is opacity, and the ways that it does and doesn’t explain. The other thing is, this piece doesn’t live on the internet forever. The research does, and all of these talks do, but with this piece, I can choose. I can choose when it goes up or down.

Towards the last third of the piece, you start layering all of these different things on the screen, among them a looped 10-second video of waves lapping and a voice memo where you talk about going for a walk with your mum. You also scroll through Merle Woo’s “Letter to Ma,” from the feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, at your own pace. All of these thoughts and feelings crescendo with Aditi’s healing song, which you play on top of everything. How did you go about structuring that climax?

I think it was definitely intuitive and instinctive, but I think there’s something about… something about having an untidy desktop that I want to talk about! I really believe in the idea of the body as an archive—you trust that the things that are meaningful to you stay in your body. All of the things you describe were the things that were living in my body at that time, and they were really alive.

I’ve also been doing loads of Zoom teaching, and it’s kind of how I teach: the mess behind whatever screen I have decided to display looks like that! I didn’t necessarily have a structure of where I wanted the piece to go, but I would move with the energy of the space. It’s about liveness. The other layer to it is this song, “Siyabulela” by Asher Gamedze. He’s a jazz musician, and this incredible scholar and thinker and activist who came and talked to a class that I was part of last year. In the liner notes for that song, he talks about it as a song of mourning, about grief and letting go. But it’s also about healing and joy. I didn’t know that when I put the song in the piece; Aditi [Jaganathan] had sent it to me. I think what you described is like a constellation of ideas that connect but could say different things at a different time, and I really like trying to teach like that.

I think that goes back to refusal as well—there isn’t one way to make different connections, to tell the story, to watch that piece, to understand that piece, and there isn’t one way of me making it. If I were to make it again, there would be a totally different set of references and maybe a different order, or a different mess on the desktop, I guess.

One of the other artworks you reference is a short film called MEDICATED SUMMERS / BENEFITS TRAP / ENDS PORTALS by free.yard aka Adam Farah, which you first played as part of the ICA performance. You describe it as a portal.

There’s a lot of stuff that got evoked by watching free.yard’s piece, which is this really beautiful slow walk down a high street in Wood Green [in North London]. It’s a London that isn’t pretending to be anything; it’s just the London that I’ve grown up around. The experience of watching that was really important. The first time I saw it was at The Experimenta Debate that Rabz Lansiquot curated [as part of the 2019 edition of the London Film Festival, where Jemma used to work]. Rabz had brought together only Black and brown artists, and most of them were from London, so there was this sense of locality. Something switched in my brain at that moment, like, I can be who I am here.

It also features a kind of music that I love. “Stronger” by Sugababes is this really emotional pop song.

And it’s the live, acoustic version of that song, from a performance on [British chart show] Top of the Pops. It’s a more vulnerable version of this very moving song. That free.yard piece makes me cry.

There’s so much emotion in it, and so all of that got connected in my head, like, “I’m feeling so much in this place, at the ICA, in this cinema where I’ve done work for years, and I’ve made myself feel nothing here.” There was this moment where I thought, “Oh my God, I’m remembering who I am and I’m feeling a lot.”

In terms of the portals, going back to the mushroom trip, a lot of that trip was in this room with a window that [looked out onto] a massive tree. That square of green with the tree would change, and I would get pulled into different parts of the trip. There’s also a window in my study in my house which also has a massive tree in its view.

You can see that tree in the background of this video piece.

Exactly. That’s kind of in reference to the portal. That piece was a portal into a different way of being. Being a programmer for all those years didn’t account for me, didn’t account for my body, didn’t account for my lived experience. Watching it was like Oh, this is why you do it. So you can feel this.

What else have you learned in making the piece?

That I can’t force people to hear or understand or to listen. I can’t speed up the change. All I can do is continue to try and understand myself and others more, and potentially create spaces for others to do the same.

There’s one more thing I want to talk about and it’s the title, which quotes “There Are No Honest Poems About Dead Women” by Audre Lorde. You both ask, “What do we want from each other after we have told our stories?” Lorde’s tone is cautionary—she delivers it like a warning. When you titled the piece after that question, did you mean it as an earnest provocation? Or were you asking with a raised eyebrow?

The reason I know about that poem is because I was doing all this research on motherhood and I made a podcast about revolutionary mothering. I read Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution by Adrienne Rich, who was a radical feminist in the ’70s and a contemporary of Audre Lorde, except she was white. She talks about lived experience—what is lived experience if we are not thinking about the wider connotations of lived experience? It’s a bit like what we’ve been talking about: when is it just sharing trauma in public, and when is it something that is important to share? Why am I sharing this in public, and what is required of me now?

Using her voice and not my interpretation of her voice is also a reminder to me that it’s not just about me. The personal is only political if it’s collective, and it’s a collective concern. Otherwise, just keep it to yourself. The real use of this work being out there in public is that it could potentially break a cycle and dismantle something harmful. That’s what you do after you’ve told your story.

***

Simran Hans is a writer and film critic for The Observer in London.

Stills courtesy of artist Jemma Desai and Lux