My first exposure to the late musician Arthur Russell came when I was working as a press intern at the British Film Institute in January 2009. I was asked to burn a DVD screener for the feature debut of the young documentary filmmaker Matt Wolf, entitled Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell, which was just about to play at the BFI’s London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. Intrigued by the title, I gave the disc a spin, and was quickly enraptured by Wolf’s tender evocation of this enigmatic figure: a gay avant-garde composer, singer-songwriter, cellist, and disco producer who, before his untimely death from AIDS in New York in 1992, left behind an extraordinarily rich, genre-defying body of music.

In the intervening years, Wild Combination’s subject and filmmaker have both grown in stature. Russell’s music, under the stewardship of his former partner Tom Lee and Audika Records founder Steve Knutson, has continued to see the light of day in a semi-constant stream of posthumous releases. He’s been sampled by Kanye West and covered by dozens of contemporary artists; his music has featured in multiple films (including, prominently, Ira Sachs’s 2012 drama Keep the Lights On), and he’s now widely regarded as one of the most important and influential musicians of the 20th century.

Wolf, meanwhile, has developed an impressive body of nonfiction work that is distinguished by its sensitivity and thoughtful deployment of deeply researched archival materials. He has made revelatory films uncovering hidden queer histories (I Remember: A Film about Joe Brainard, Bayard & Me, Another Hayride), and keen portraits of ambitious eccentrics seldom understood in their own time (Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, Spaceship Earth). Wolf’s next project sees him take on the complex legacy of Pee-wee Herman performer Paul Reubens in a two-part documentary for HBO.

Arthur Russell would have turned 70 on May 21, 2021. So, to loosely mark this occasion, I caught up with Matt Wolf to reflect on his experiences of discovering Russell and making Wild Combination.

When did you first find out about Arthur Russell? When was your first exposure to his life and work?

Shortly after the compilation [album] Calling Out of Context came out in 2004, my friend, the author Jeremy Atherton Lin, told me about this gay disco auteur who would ride the Staten Island Ferry back and forth, listening to cassette-tape mixes of his own music, and that image really intrigued me. I went to Other Music in Manhattan [a former retail store], and I bought the CD—this is maybe a year after I’d finished college. I started listening to the music and was completely absorbed and obsessed with it. I remember driving over a bridge with some friends. The title track was playing, and I just thought to myself: this is what I care about. This is what matters to me. It felt very clear.

When I started making the film, there was definitely a mystique around him, because he made this incredible music that wasn’t known. He had the aura or reputation of a contemporary artist. It felt like new music that was being made in that moment, not like old music that was being reframed.

And how did the film project flow from this initial revelation?

I did something that now I do all the time as a filmmaker, but had not done before: I wrote a letter to Tom Lee, Arthur’s partner. There’s this thing called the NAMES Project, which lists the executors of the estates of artists who died of HIV-AIDS, and I found Tom’s address; he lived in the East Village. I wrote him this naïve letter, because I had not made a film before. But I wrote it from the heart, about why I loved Arthur’s music, what my intentions were as the filmmaker, and why I wanted to do a project about him. I viscerally remember the answering-machine message that Tom left for me. He sounded so sweet and kind on the phone. The idea that you could write someone a letter and two months later get a phone call and a message was exhilarating to me because this was the first time I had engaged in that kind of process of outreach. The more primitive term is to “gain access,” but really it’s about building a relationship with somebody whom you intend to ask permission to make a film about, or ask their blessing to make a film about somebody who can’t give that permission themselves.

I went over to Tom’s apartment in the East Village. At the time I had no idea, but it was this legendary building that Allen Ginsberg and Richard Hell had lived in. I believe Richard Hell still lives there, and Tom lived in the apartment he shared with Arthur, where much of Arthur’s music was made. We just had a really nice meeting. I think part of why we connected is because I’m gay, and I was curious and interested in understanding Arthur as a gay artist who had prematurely died of AIDS, and not just as a musician. The distinction between “artist” and “musician” can be blurry, but there’s definitely a music-nerd culture that is attached to artists like Arthur. I was coming to this from a lot of interest in contemporary art, performance art, queer history, the history of downtown New York, the intersection of pop and avant-garde music and culture of that period. For whatever reason, Tom gave me his permission to do it. I also had to seek permission from Steve Knutson of Audika Records, who also generously went out on a limb and believed in me.

To what extent did you have an idea of the style of film you wanted to make going into the project?

When I first conceived of the project, I definitely thought of myself more as an experimental filmmaker. I had gone to NYU Film School and had really rejected feature filmmaking by the end of it, because I hated the experience so much. I was in a video activist collective called Paper Tiger Television. I was working with queer youth and homeless queer youth on making community-based media. I was writing criticism for art magazines and was very submerged in the experimental-film and video-art worlds. I just was anti-mainstream filmmaking, then I took my senior class with Kelly Reichardt, which shifted how I thought about filmmakers as artists, and how you can work in a space of so-called mainstream filmmaking and also be an artist.

I remember writing something to myself: “I don’t want cultural material to just be something I care about. I want to know it so well that it becomes part of my life experience.” Meaning: I don’t want to just have a short-term fascination or interest or obsession with something. I want to get involved with it, whether it’s a biography or music or archive; I want to get so involved that it actually becomes part of the story of my own life.

How did the form of the film come together?

When I received permission to work with Arthur’s material, at first I thought: “Oh, I’m going to make a video record. Each chapter will be a different element of Arthur’s life or career. There’ll be a disco chapter, and it’s a video installation on one wall. Then another chapter is [on 1986 album] World of Echo, and that’s a video on another wall. There would be an expanded video-art installation that would come on a DVD.” My collaborators, whom I had gone to NYU with—we were all 23 years old at this time—were like, “You’re making a documentary.” I said, “I’m not making a documentary. I’m making a video record. It’s not a feature film. Everything doesn’t have to fit in the box of a feature. That’s not what I’m doing.”

Did you have a negative perception of what we might think of as traditional documentaries?

Part of me did have this intrinsic bias that documentaries were very conventional and static. But the first thing I shot was an interview, and I had this sense of confidence that I’d done it well. The more I interviewed people, the more passionate I became about developing that process—the artistry and craft of the interview. In time, I started to realize that interviews are not stodgy; they’re an emotionally intense way to reanimate history, and that when you venture to make a portrait of somebody who’s absent, and who is mysterious by nature, the composite impressions of all these different people brings them to life. At some point I acknowledged I was making a documentary, and thought: how can we do a documentary in a way that is about an artist, but from the point of view of that artist?

And how did you attempt to tackle that conundrum?

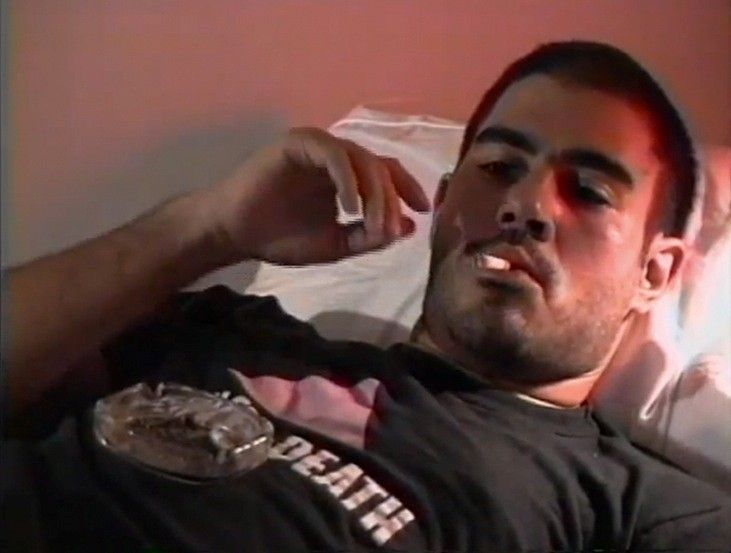

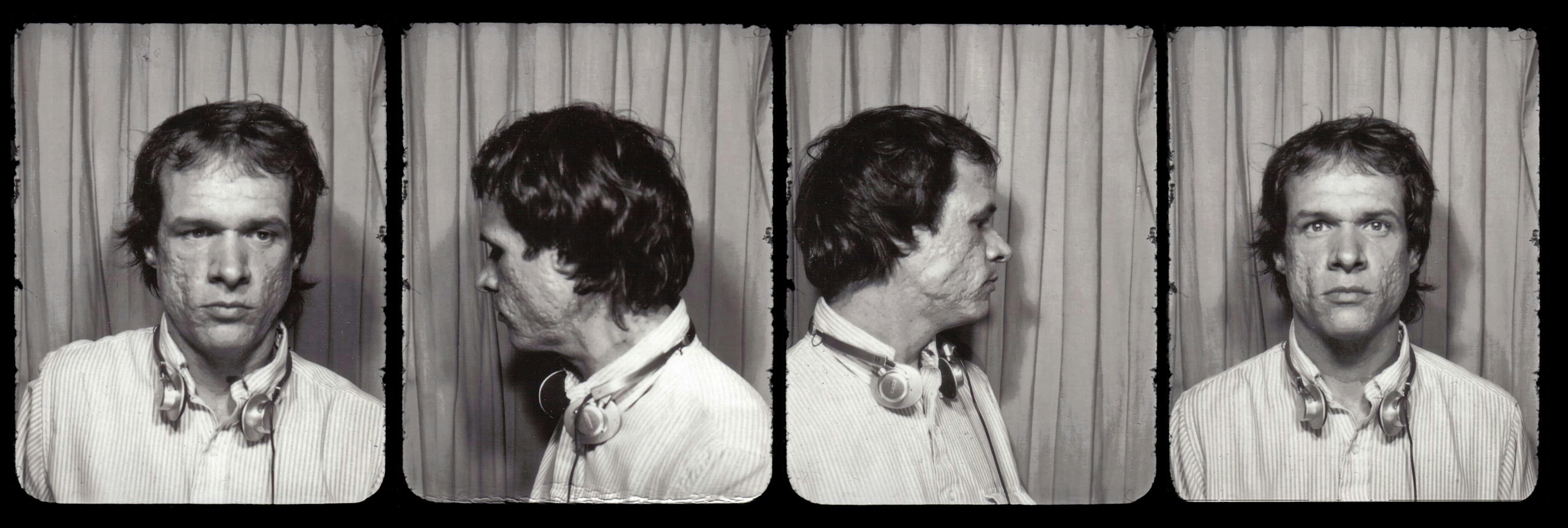

Part of me felt unsure if I could make a feature-length documentary about Arthur, because there was so little primary-source material of him. But the idea of doing recreations appealed to me because of my obsession with the image of this guy riding the Staten Island Ferry back and forth, listening to mixes of his own tapes. The cinematographer on Wild Combination, Jody Lee Lipes—a very acclaimed cinematographer today—suggested that we buy a VHS camera and play with it, so we did. It had these glitches that created dropouts in the video image, which would become desaturated and then slip into this saturation. I remember going onto the Staten Island Ferry and shooting VHS stuff of the ocean: the color would suck out of the ocean and then seep back in with a cyan look.

Some of the only existing archival footage of Arthur Russell is from a performance he did at [intermedia artist] Phill Niblock’s loft in Soho, and that was also desaturated, VHS, extreme-close-up footage of Arthur—really intimate documentation of World of Echo performances. I wanted my recreations to look like this, so the VHS camera became a diaristic way to retrace Arthur’s footsteps. That recreation became an important learning experience for me, in particular the one on the Staten Island Ferry. The costume designer was Janicza Bravo, who is a well-known director today. She went with me to Tom Lee’s apartment, and I borrowed Arthur’s actual jacket. My boyfriend plays a young Arthur, and she got him this young Arthur outfit. I still have the backpack she bought in my closet. I sourced cassette tapes and headphones that looked exactly like the ones I’d seen in photos. As this process progressed, it became clear that it wasn’t just a construction to illustrate [the] film. It was about tracing the footsteps of somebody whom I could never get that close to, but whom I wanted to get as close to the spirit of as possible.

Something I find notable about your film is that it makes Arthur—who, in his lifetime, was an enigmatic figure who released music under a bewildering array of different monikers—clear and legible, but not in a way that seeks to put him in a particular box.

That is 100% what I learned about how to be an artist while making that film. There are many different sides to us, but the culture expects us to express ourselves as a single person on terms that are coherent and legible across time. It takes a certain kind of bravery and confidence to allow yourself to explore all the dimensions of who you are. In fact, Arthur did that by organizing his different impulses with different monikers, whether it was Dinosaur L or Loose Joints.

As a filmmaker, I like subjects who pursue projects with a level of complexity that doesn’t make sense to people in their moment or in their time—this is true for the archivist Marion Stokes and the characters [who quarantined for two years in an eco-dome] in Spaceship Earth. Part of my job as a filmmaker is to step back and act as a translator, to help create a coherent narrative around multifaceted projects that can’t be simply or neatly summarized; often, the lives of visionary people are narratively incoherent.

I love how you begin the film with a passage featuring Arthur’s parents—there’s an instant foregrounding of the primacy of care and familial love, rather than “here’s this cool musician…”

I met Arthur’s parents, and I thought they were extraordinary: these people from Iowa, from this generation, who were unconditionally supportive of their gay son making avant-garde music that nobody understood. He died of AIDS, and they wanted to preserve and build understanding for his legacy. That was intensely moving, as was the fact that they had embraced Arthur’s partner and maintained a relationship with him. I felt those things, and I trust that if I feel moved by something, then other people will too. I feel so emotionally involved in that film. Honestly, I haven't watched it in a decade, because it’s hard for me to watch it.

I remember the intensity of those feelings. Not only were they feelings that were unique to this subject and the relationships that surrounded Arthur, but for me, it was my first time doing this, and it was so intuitive. The relationships I built were so formative that it’s even hard for me sometimes to listen to Arthur’s music. When I make films, there’s a certain level of intensity in those first visceral connections I feel with subjects, and a sense of urgency to help other people see and feel what I see and feel. For me, what matters most is the emotional experience of my films, and the only way I know how to do that is to have a strong, emotional connection to what I make my films about.

How do you look back on the film from a contemporary vantage point?

In terms of what’s changed, I think the circulation of information about hidden histories, like Arthur’s, is different. Today I would have found out about Arthur on a music blog long before a friend would send me a letter and tell me this mythical story of a gay disco auteur on the Staten Island Ferry. I would’ve easily found Tom Lee’s email and gotten a response quickly from him. The way information is transmitted is just different [now], and so the sense of discovery that I had with Arthur was special.

Clearly, it’s like Arthur was an invisible mentor to me. He taught me so much about how to be an artist and how to exist in the world with integrity toward what you care about, and to be uncompromising. I also learned from Arthur how to exist in a space that’s avant-garde and experimental, but that also aims to be mainstream. I want my films to reach a broad audience, and I want to grapple with complex ideas and mercurial subjects that aren’t assimilated or dumbed-down for people. I think that desire to do something with integrity and complexity, but to also reach an audience and to operate within the language of popular culture, is something important to me that I learned from Arthur.

Listen to a special Arthur Russell playlist curated by Ashley Clark.

***

Ashley Clark is the curatorial director at the Criterion Collection. Previously, he worked as director of film programming at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and he has curated film series at BFI Southbank, the Museum of Modern Art, TIFF Bell Lightbox, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, among other venues. He has contributed writing to publications including Film Comment, Reverse Shot, Sight & Sound, and The Guardian. His first book is Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s “Bamboozled” (2015).

Stills and photos courtesy of Audika Records and Oscilloscope Laboratories.